HighLoad Saga. Part Two, Chapter 1: Storing the Data

Modern tools and technologies are no longer fit in classical DBMS categoris.

DBMS is database management system. The software like PostgreSQL and so on.

These technologies, optimized for broad scenarios, continue to blur traditional boundaries.

For instance, in-memory key-value systems like Redis can surprisingly serve as message queues, while systems like Kafka offer message queues with added storage reliability.

Addressing complex System Design challenges involves decomposing them into smaller problems and applying a wide range of tools.

This includes using additional layers like Memcached for caching or Elasticsearch and Sphinx for full-text searching, which operate separately from DBMS.

Synchronizing these caches is crucial to ensure data consistency and non-contradictory results for users, and maee it so is a responsibility of our software.

Modern apps often build on a layered data model approach, each layer presenting its data to be correctly understood by the next.

This complexity increases as systems scale, despite abundant resources on relational data modeling.

So, choising right data model is greatly influences the functionality of the software based on it, it is extremely important to choose a model that is suitable for your specific task.

Yet, the industry frequently defaults to relational models and SQL, and I am woundetind = if this approach is always appropriate?

Lets take a look at some of approaches focused on data storage and query execution, probably we will find the answer for this questions.

SQL data model

The well-known SQL data model, created in 1970 by Edgar Codd, organizes data into tables.

However, it faces an object-relational mismatch.

Almost every mainstream framework, especially in web development, offer an object-oriented approach, which implies mapping the structure of objects to the fields of relational database tables.

As a result, we have a clumsy intermediate layer between objects and the database model which is pretty hard to formalize good enought.

This disjunction between fundamentally different computational models is also referred as impedance mismatch.

Impedance mismatch is only partially addressed by ORM tools. They tries to eliminate the differences between the two models, but just not able to do it, introducing more complexity and inefficiency.

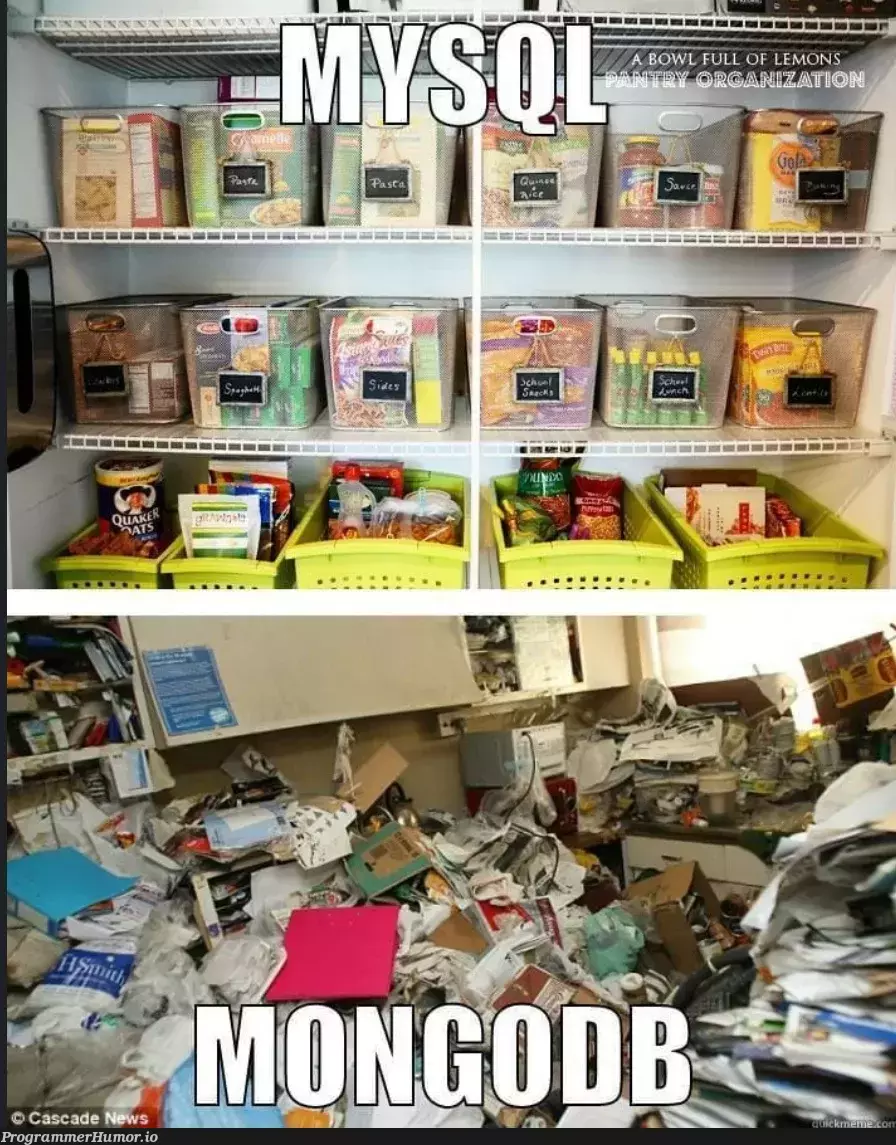

Oh, hello there - NoSQL!

That the poing where NoSQL data bases coming onto the stage.

What is NoSQL? Well, it is database management systems which are sotres unstructured documents. That why such database called as document-oriented.

JSON-representations are have better locality compared to a multi-table schema.

Locality means that all related data for some record is stored in the same document, it just all in plase.

Whereas, to be able fetch all needed data about some entity we will probably forced to make several queries or come up with some complicated “all-side” joins of that entity table with all related tables.

For example relations “one-to-many” of some user profile with all the other related, detailed characteristics imply a tree-like data structure, and the JSON representation makes this structure explicit and clear.

While storing all the related data in one JSON documents might be handy, there is a significant drawback of data duplication.

In a JSON document-oriented database, you might store each employee’s information in a single document like this:

{

"employeeId": "E123",

"name": "Pepe the Frog",

"department": "Platform Engineering",

"role": "Backend Developer",

"contact": {

"email": "pepe.feels-good@froggie.croack",

"phone": "555-1234-666-99"

},

"projects": [

{"projectId": "P1", "projectName": "Project Alpha"},

{"projectId": "P2", "projectName": "Project Beta"}

]

}

This results in massive data duplication:

-

The details of “Project Alpha” and “Project Beta” are replicated in full for each employee involved, rather than being stored once and referenced many times.

-

If project details change (e.g., the name or deadline), they must be updated in every employee document that includes that project, increasing the risk of inconsistent data.

-

This duplication can lead to increased storage requirements and slower queries as the amount of redundant information grows, especially in larger organizations with many employees working on the same projects

The idea of eliminating duplication lies at the heart of the database normalization concept.

But data normalization often requires organizing “many-to-one” relationships, which fit poorly into the document model.

In relational databases, it is considered normal to refer to rows in other tables by a unique identifier, since performing joins is not a problem.

In document-oriented databases, tree-like structures do not need joins, and if support for joins exists, it is often very weak.

When the database managment sysmtem does not support joins, they must be performed in the application code through a set of database queries.

There is another relations type - “many-to-many”. Suth relations a regular case in relation database, but for NoSQL there has been an endless discussion on how best to represent “many-to-many” relationships.

Essentially, in the scope of this question we are going back to the very first days of digital database systems.

It is CO-DA-SYL, Harry!

Back in the 1960 there was hierarhical DBMS called IBM IMS.

It was a pretty good with “one-to-many”, just like modern document-oriented dbs, but “many-to-many” was not an option for IBM IMS at all, as also it was not supports joins at all.

There was a huge volume of denormalized, duplicated data, and developers spend a lot of time trying to controll data actuallity.

To get rid of hierarhical model limitations there was proposed a few solutions. The two most know - relational model (later formed as SQL) and network model CODASYL.

The CODASYL model became a generalization of the hierarchical model, in whose tree-like structure each record had exactly one parent record.

In the network model, each record could have multiple parents. This made it possible to model “many-to-one” and “many-to-many” relationships.

The “links” between records in the network model was not like relational model’s foriegn keys, but more something more like a pointers in programming languges.

The only way to query some recoed was a traverse from the root record all way through these links.

It the trivial scenario it was the same as traversing a linked list - with a O(N) complexity we are going throug all the nodes until we find one we are looking for.

But CODASYL was designed for more than just simple scenarios. As mentioned, it accommodated “many-to-many” relationships, meaning there were multiple “routes” leading to a single record.

Developers working with the network model had to be mindful of these complex access paths, as modifying the database’s schema could easily disrupt them.

Eventually, members of the CODASYL committee acknowledged that navigating through an n-dimensional data space has a very high algorithmic complexity.

So, on the other hand, relational model exposed all the data as it was - tables is just a set of tuples, without any complex “labirints” should be passed to access required data.

But here we go again…

Despite historical challenges with hierarchical and network models, NoSQL databases are gaining more and more popularity.

Why is that?

-

We need to scale, and sclae fast!. Much quicker than relation database are capable of. We need to process very large data sets or have very high write throughput;

-

We might need to make a specialized querie that are poorly supported by the relational model;

-

We are disappointed by the limitations of relational schemas and we want more dynamic and expressive data models.

Document-oriented databases now are going back to hierarhical model, primarily in terms of storing nested records - “one-to-may” stored in the parental record, without orginizing any separate “table”.

But is we want to come up with “many-to-many”, or “many-to-one”, well… relational and document-oriented databases are not significantly differs in their approaches.

In the both of these scenarios query for requeired element is performed with the help of unique idenitfier, which is a “foreign key” in the relational model, and a “document reference” in the document model.

This identifier is resolved at read time through joins or additional queries.

Document-oriented database are not following the path laid by CODASYL, and generally, I guess it is fine.

Document versus Relation

If our application’s data structure is document-like (i.e., it represents tree of “one-to-many” relations, usually loaded all at once), using a document model is likely a good choice.

The relational model enhances productivity for “many-to-one” and “many-to-many” relationships, albeit with some theoretical limitations. For instance, it requires shredding—breaking down the document-like structure into multiple tables.

When choosing a document-oriented database, consider the following:

- Direct references to nested elements within a document are not possible in the document model. This requires encoding paths in a way reminiscent of the hierarchical model, which usually isn’t a problem if document nesting is limited to few levels (2-3).

– The lack of robust support for joins in document-oriented databases may or may not be an issue, depending on the project. For instance, “many-to-many” relationships may not be necessary for a content management system where articles are stored with embedded comments. But this limitation becomes significant somthing like social networking apps, where complex “many-to-many” relationships between users and groups are essential.

- Reducing the number of necessary joins through denormalization is possible, but it requires extra maintenance work to keep the denormalized data consistent.

Database Schemes

Most document-oriented databases, as well as relational databases in scenarious of using JSON or XML records, do not enforce a specific schema to define a unified data structure within documents, unlike the strict structure defined for tables in the classical relational data model.

The absence of a schema allows us to insert any keys and values into a document, and when reading these documents, we have completely no guarantees or annotations explaining what fields are present in it.

Thus, document-oriented databases are often referred to as unstructured, schemaless, among other terms.

Such schema-less approach is called schema-on-read. It implies that the data structure is implicit, and data interpretation occurs when records are read from the database.

Conversely, schema-on-write is the traditional approach of relational databases, always having a clearly defined, guaranteed data schema that all written data must match.

Schema-on-read is similar to dynamic type checking in programming languages, whereas schema-on-write resembles static type checking.

There’s no definitive for this “holywar” question, answering which approach is better.

Data Locality and Queries

Documents are stored in the database as continuous strings, serialized into JSON, XML, or their binary variants (BSON in MongoDB, or JSONB in PostgreSQL).

If an application frequently needs access to the entire document, data locality offers advantages: a single query can retrieve the whole hierarchical structure.

If data is spread across multiple tables, multiple queries and index searches are needed to fully extract them, requiring more disk operations and taking more time.

Data locality is only advantageous when large parts of a document are needed at once because the database has to load the entire document, even if only a part of this document is needed.

This is inefficient.

Updating a document, almsot in all cases requires rewriting it entirely.

Therefore, it’s generally recommended to minimize document size and avoid write operations that increase size when working with document-oriented databases.

These performance limitations significantly narrow the scenarios where document-oriented databases are more useful than relational ones.

And because of it relational and document-oriented databases are becoming more similar.

It seems the future lies in hybrids of relational and document models.

PostgreSQL, in particular, handles JSON brilliantly already!

Query Methods - SQL

SQL is a declarative language that was a breakthrough for the relational model, while IMS and CODASYL used imperative code for their queries.

In declarative query languages, a “pattern” of expected data must be described. We set conditions for the resulting data and, posddibly, conditions on how this data must be transformed (sorted, for example).

SQL does not give a heck on how the results should be achieved.

The decision on which indexes and join methods to use and in what specific order to execute parsed parts of a query is made only by the database managment system’s query optimizer.

Thus, declarative languages are well-suited for parallel execution as they define only a results pattern, and not the algorithm for obtaining them.

Graph Data Models

Through our exploration, we’ve seen that hierarchical models don’t fit well with “many-to-many” relationships, and relational models only handle the basics of these interactions. As data connections become more complex, using a graph to model this information feels more intuitive and efficient.

In a graph, there are two primary elements: vertices (also known as nodes or entities) and edges (also referred to as relationships or arcs).

Graphs can shape various data types, not just those that are similar. They are powerful in combining different kinds of object data within one storage solution.

Take Meta as an example, which uses a unified graph structure filled with diverse vertices and edges. Vertices symbolize individuals, places, occasions, system entries, and comments made by users. Edges reveal connections like friendships, specific login locations, comment authorship, event attendance, and more.

Think of a graph database as composed of two relational tables—one for vertices and another for edges. Properties of vertices and edges might be stored using data types like json. Information on the starting (head_vertex) and ending (tail_vertex) points of edges is kept, making it possible to swiftly access all incoming or outgoing edges related to a particular vertex by querying the respective fields in the edges table.

Key features of this model include:

-

Any vertex can link to another through an edge without restrictions on the types of connections.

-

It’s possible to identify both incoming and outgoing edges for any vertex, allowing for navigation through the graph in both directions. This is why indexes are placed on both the tail_vertex and head_vertex columns in the edges table.

-

Utilizing varied labels for different relationship types enables the storage of diverse information in a single graph, keeping the model’s structure clean and organized.

Wrapping up

We’ve taken a good look at how we keep and find our digital information. We’ve seen that old ways like SQL databases aren’t always enough anymore, and that’s why we’re seeing more use of graph databases. These new methods are like a fresh coat of paint in a world that’s always changing and growing, just like how Meta is doing things now.

And we’re not done yet! Next time, we’ll dig into the nitty-gritty of how data is stored, talk about what “key-value” means, and explore all sorts of indexes. We’ll also tackle big concepts like SSTables, LSM-trees, and B-trees, and we’ll try to make sense of how to make everything run faster and smoother. So, stay with us as we keep on exploring this HighLoad adventure. There’s a lot more to come!