Attention, We Have a Gap!

March 17, 2025

Intuitions Are Experience

Generally, awareness of the gap with reality between the phenomenon we are reasoning about (event, object, task, situation) occurs intuitively.

This is a very quick, almost instant process, it feels more like a sensation than a clearly formulated, focused awareness.

Such tasks are processed by fast System 1 thinking according to Kahneman,

which compares facts/features related to the evaluated phenomenon with facts/features from a certain “database” that is filled with our explicit and implicit subjective experience gained throughout life and our work in various applied domains.

System 1 thinking according to Kahneman is an automatic, fast, and intuitive way of thinking. It works without conscious effort, based on associations and heuristics, allowing us to react almost instantly to situations. This thinking requires little energy, is based on habits/experience, and is highly affected by cognitive biases.

When fast thinking finds inconsistencies, we feel it vaguely as “something’s off,” “they’re talking/suggesting nonsense,” or conversely in extremely oposite situation, if we hear consistencies – “I feel in my heart that this is the holy truth, everything is right!”.

But mostly we feel this in “mismatch” scenarios. When everything is “alright” we likely just turn a blind eye to it. It is fine after all, right?

It’s very important to pay attention to both of these feelings, especially the feeling of wrongness. Anatoly Levenchuk in his manuals of Engineer-Managers Workshops suggests a very precise term for this feeling - “ontological buzz.” Recognizing ontological buzz is important because it’s a clear indicator of some gaps between perceptions and reality, or between perceptions and other perceptions (your own or others’) – both types of failures need to be caught, grounded, fixed. It matters to react immediately, because if the buzz is happening, that means there is already something wrong, in the best case - only in your mind, but almost always it is a problem in collaborative ontology.

Out basic intuition develops “on its own along the way,” although it can and must be improved.

Master’s Intuition

A master’s intuition is another type of intuition that doesn’t quite develop on its own, but rather the opposite.

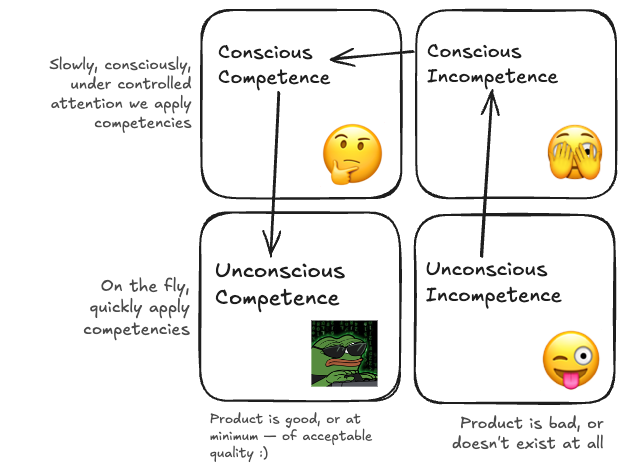

Such intuition is a painstaking process of transitioning from unconscious incompetence to unconscious competence, where the latter is precisely the “master’s intuition.”

There’s a “competence square” that perfectly illustrates the path along which this type of skill develops:

At the very beginning of our working in a new domain, when we’re just learning a new blob of information and “how to do things here,” we can’t even say what we don’t know. This is unconscious incompetence.

Gradually, we develop skills and mastery until this new mastery is honed to the point where we become able to apply it automatically.

At this stage, we begin to notice inconsistencies in our own or others’ words (spoken or written), documentation, and other sources of information when it comes to the domain of our mastery.

If we have problems with emotions and self-control, then possessing such a degree of applied mastery can lead to “getting angry at the idiots around me,” and this is a big problem, a huge topic for a separate conversation. In any case - pay attention if you notice such consequences of ontological buzz in yourself, this is a destructive pattern and generally a sign that you need to work on ‘basic mastery’. There can be many reasons, both biochemical (simply problems with hormones that you don’t know about or know but don’t allocate enough strength and attention to deal with them), and psychoneurological. In any case, it is a good idea to seek professional help here.

The “Fundamentally First” Skill of Catching Ontological Buzz

Both types of intuition are needed and important; it’s useful for us to know about them and consciously develop.

Timely awareness of ontological buzz is one of the basic skills of applied mastery of focus that is very important for us to hone.

The problem here is that we can too often either not be aware of these inconsistencies at all, or let them “go in one ear and out the other.”

Such bypassing happens because we don’t realize how important an indicator this ontological buzz is, and we don’t know how to work with it at all. This is expressed in feelings like – “Uh, they’re not quite right, they don’t quite correctly understand ‘the thing’, damn… how can we even come to an agreement? I’ll try saying the same thing in different words several times, maybe that will help”

After 15-20 attempts, we are giving up because “it’s impossible to agree and work with this colleague, they just don’t understand anything.”

The thing is, just repeating your viewpoint with different words will not help. Ontological buzz happens when there are gaps in the professional languages you and your colleagues are using, or because there is no such ontology at all. Catching these buzzes is the signal for an urgent need of ontological modeling, which if integrated into the system and properly supported will help everyone stay on the same page, talk and work productively.

Well, now (hopefully) we’ve realized the importance of catching this buzz.

But still – how do we work with it? This is the main cornerstone of ontological engineering, for now we already know one of the first principles:

Ground the gap between perceptions and reality.

You can start by capturing semantic patterns in communication with colleagues, and in communication with “yourself”:

- A vague, stumbling answer to a question – an answer without confidence, with stutters, hesitations. Lack of confidence and specificity in the answer may, and often does, indicate that the words are poorly connected to reality;

- Phrases like “sort of possible,” “well, in principle, we’ll do it,” “theoretically doable” are present – the loudest signals of a disconnect from reality, requiring immediate intervention.

- Too long, drawn-out answer to a quite specific question – the respondent either didn’t understand the question, then we need to clarify it ourselves. If after clarifying the question the answer is still too vague – we need to pay closer attention;

- And conversely, too quick an answer to a question which (as we know) requires some analysis and reflection – for example, the universally loved task estimation, where the developer instantly replies “I’ll do it in two days”;

- Vague phrases without any grounded specifics – “we’re making a digital product,” what kind? “we’re developing fintech API” - which one? what features? “We’re producing packaging” – what kind? Cellophane bags? Cardboard boxes? Dry containers made of nodular cast iron for radioactive rods?

These are basic examples to start with. As we develop mastery in attention to ontological buzz, we develop our own signals, you could say we’re filling that “database” for intuition that we talked about earlier.

Next time we’ll talk in more detail about “grounding” itself, “reality,” how to see them, and what might prevent us from seeing them clearly.

If you found this material even somewhat valuable – please follow me wherever you like: https://links.ivanzakutnii.com